According to Canadian War Museum historian and author Tim Cook, though the current climate honouring soldiers who fought in the Second World War is quite positive, it hasn’t always been that way.

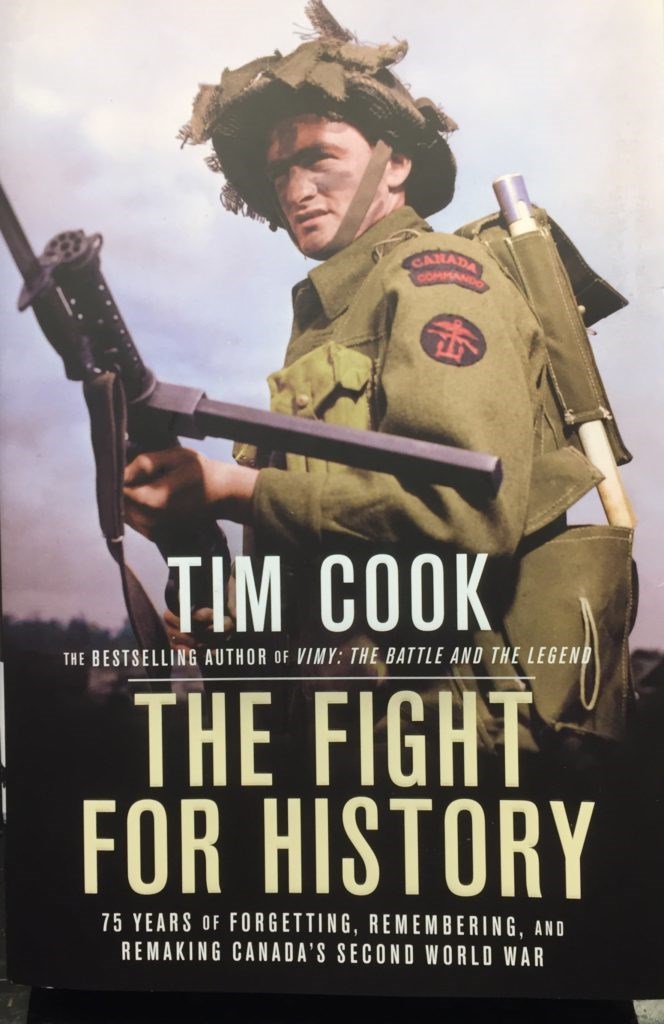

His latest, The Fight for History: 75 Years of Forgetting, Remembering and Remaking Canada’s Second World War, looks at the struggle of veterans, often through organizations such as the Royal Canadian Legion and the War Amps, to be recognized and honoured for fighting for their country. Through a number of government administrations, it continued for years to be a difficult fight.

Throughout the exhaustively researched book, Cook points out the differences between the country’s post-war reaction to the two World Wars. Though the importance of Vimy Ridge rose and fell in the public eye following the First World War, Cook posits that for the most part, the Great War, as it is often called, has usually been seen as a watershed moment in Canadian history.

The formation of the Canadian Legion (the ‘Royal’ was added in 1962) was in an effort to provide a voice for First World War veterans. As well, the National War Memorial in Ottawa, dedicated by King George VI in 1939, still stands today mainly as a monument to those that fought and lost their lives in the Great War.

Conversely, Cook says for years there was a push to erect a similar poignant tribute to the many lost in the Second World War, which he terms the Necessary War. A plot of land in the nation’s capital was chosen, and sketches for a National Shrine to honour these veterans were released, but the Diefenbaker government did not follow through on promises to prioritize the construction.

Later, under Lester B. Pearson, the Prime Minister’s focus on a new flag pushed the National Shrine discussion to the back pages. Through the many administrations that followed, veterans would often hear some renewed talk of a memorial to the Second World War, but nothing ever came of it.

Cook adds that influence from our neighbours to the south may have at times devalued Canada’s contributions to the Allied win over Germany and Japan. A powerful, deep-pocketed Hollywood film industry, through Oscar-nominated movies such as The Great Escape and The Longest Day, left many with the impression that the Americans won the war completely on their own. There was little to no mention of Canadian troops of any kind in these blockbusters.

At the same time, he points out, Canada’s film industry, including the CBC and the National Film Board, did very little to herald the Second World War efforts of the country’s armed forces. In fact, when the CBC finally financed the three-part series The Valour and the Horror, it was justifiably panned, as Cook says, for painting the Canadian effort in a less-than-flattering light.

Events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Vietnam War, amidst the anti-war activism of the ’60s generation, created a generation gap. Younger people during that time were reluctant to honour the fighting of their forebears. Later, in the ’70s and ’80s, Japanese Canadians who were interned during the war continued to push for redress. In 1988, that finally resulted in the Mulroney government’s payment of $21,000 to each survivor, and more than $12 million invested in a community fund and human rights projects. During that same time, Cook speculates that the importance of Japan’s standing on the world’s economy made successive Canadian administrations reluctant to push that country for an official apology for the mistreatment of Canadian POWs at the hands of Japanese soldiers.

On the positive side, the 40th and 50th anniversaries of D-Day were high points in bringing the accomplishments of Canadians into light. As well, the inauguration in June, 2003, of the Juno Beach Centre in Normandy, France, finally shed light on the Canadian Second World War effort on the world stage. It stands today, along with the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, as reminders of Canada’s important roles in the two World Wars. Cook, though, points out how the museum began as a grassroots effort by Canadian Second World War veteran Garth Webb, and that the Mulroney government was almost reluctant in getting involved in the project.

Cook’s 11 books on Canada’s military history have earned him numerous awards, as well as a membership in both the Royal Society of Canada and the Order of Canada. His dedication to research and his work at the Canadian War Museum make him the country’s most important military historian since J. L. Granatstein.

Through the entire timeline of this important work, Cook weaves in stories of heroic efforts by soldiers and veterans both during and after the Second World War. Its 436 pages are highly readable and engaging. The 56 pages of endnotes give proof to the fact that Cook has done his homework in creating this definitive history of how Canada has treated the survivors and those not so lucky to have survived the Necessary War.

On this Remembrance Day, which marks the 75th anniversary of the end of that conflict, it’s a work that will remind all Canadians how important it is to remember.