The monarch season has begun.

As my friends know, I’ve been fortunate in recent years to raise many monarch (and swallowtail) butterflies and have shared the experience with family, students, friends, residents in long-term care homes and other groups that invite me. So many people have not seen them at the var- ious stages of transformation – some-thing that never fails to excite me.

Upon their return from over-wintering in Mexico (or the west coast ones in Califor- nia), monarchs usually have their first brood in the south- ern United States. The next generation may head north towards Canada with per- haps one more stop to breed once again, before head-ing to our area (or further north). They have had many mon- archs as far north as Thun- der Bay in recent years. On occasion, a very battered one may arrive in Ontario hav- ing made it all the way from Mexico.

This year I’ve not yet seen any adult monarch but- ter-flies, but I know they’re here. About 10 days ago I be- gan finding their recently-laid eggs in sunny places where milkweed has been planted and allowed to grow. Thank- fully, many more people are becoming aware and are not only allowing milkweed to flourish, but are plant- ing it in their gardens. Black swallowtails feed on Queen

Anne’s lace, carrot leaves, dill and pars-ley. Unfortunately, many towns, like our own, are cut-ting down what is growing along the roadside, and many of our pollinators are suffering or disappearing completely. Many farmers use chemicals that are harmful to these delicate creatures. I try to raise aware-ness, but have hit many roadblocks.

Monarchs generally lay one tiny white egg on the un-derside of a milkweed leaf and then move on to an- oth-er leaf. The mother-to-be fertilized butterfly perches on the edge of the leaf, reach- es under with her abdomen and deposits her egg. It’s ex- citing to see. After about five days a very tiny yellow, black and white striped caterpillar emerges. It may feed a bit on that leaf and then wander off to find another. It often drops from a thread (that comes out of its back end) and allows the breeze to blow it elsewhere. Somehow, it manages to find other milkweed plants, some- times wandering quite far from where it was born.

After feeding for about 14 days, it will become very rest- less, move on quite far away from where it was feeding and try to find a high, hor- izontal surface on which to transform. Outdoors, it could be the edge of the roof line. Indoors, where I have kept them in a very large jar (or butterfly cage), they will attach themselves to a craft stick I’ve laid across the top. So they don’t escape, I have had the jar covered the whole time with a piece of nylon netting. Re-

markably, they find the stick, attach themselves, and within an hour or so, drop their head end and hang quietly by their tail end. When the caterpillar begins wiggling, the skin sud- denly splits open at the bottom and within a few minutes be- gins to rise to the top and drop off. The pale green chrysalis

with its gold specks becomes visible and takes its final form within the hour.

Monarchs stay in their chrysalis for about nine days as the molecules rearrange themselves to become that beautiful adult creature we’ve all learned to enjoy. The day before the chrysalis opens, it

changes colour – be-comes dark and clear – almost trans- parent in bright light. That morning, before the sun ris- es to its peak, the butterfly breaks out of its confined area. It is born head first and hangs there as its wings start to expand. As it cannot fly for the first one or two hours, one

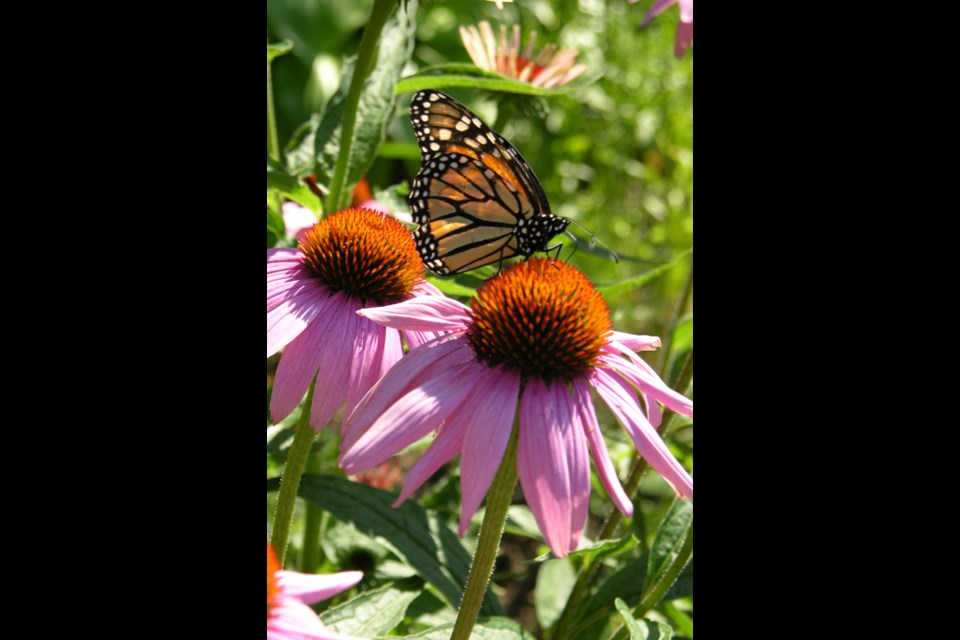

can coax it onto a tiny branch and carry it out to a safe place, perhaps putting it onto a flow- er branch to allow its wings to dry out completely. If you are lucky enough, as we were, it may even come back to you, land on your shirt as though to say good-bye, and then fly away to find a partner.