The concerns of rights and living conditions for seasonal farmworkers is one not easily resolved, although there are several processes in place intended to ensure consistent standards and treatment for all.

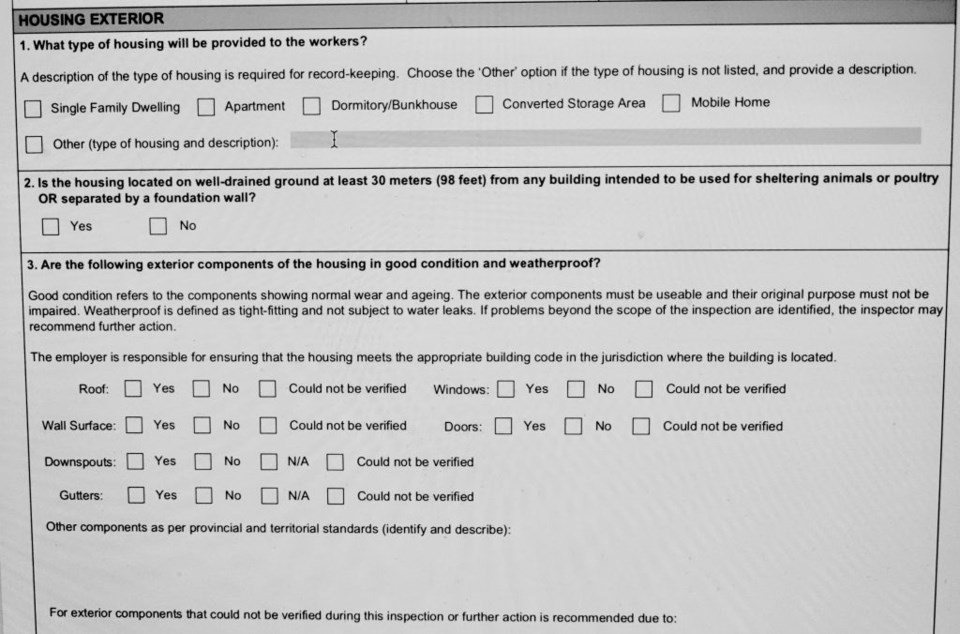

Public health units are in charge of housing inspections, and are following a checklist of conditions, with the results reported to Service Canada, says Glen Hudgin, regional supervisor for living inspections.

Federal ministries are charged with other issues, such as labour problems, and there are annual reviews involving officials from all countries involved in the temporary workers program, says Ken Forth, president of the Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Services (FARMS), the non-profit organization that administers the program in Ontario. Those reviews are intended to highlight any problems, and find solutions, he says.

Yet we still hear of concerns over living conditions, and worse — workers badly treated, sometimes sent home if they complain or if they’re sick or injured, some too scared to lodge complaints or speak out, with families depending on the income they earn in Canada.

Hudgin is the manager of environmental health for Niagara’s public health department. It is his job to supervise inspections of housing for temporary farmworkers, and to report to Service Canada. If housing doesn’t pass any one of many items checked during a detailed inspection, public health notifies the farmer, who must make necessary improvements to pass inspection with zero infractions before being allowed to hire temporary workers through the federal Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP), he says. Included in the extensive list of checks to tick are the size of the rooms, the availability of bathrooms, showers, sinks, stoves, and many other factors that also determine how many workers can be accommodated, says Hudgin.

His department has inspectors working pretty much year round, checking out living conditions to meet the varying timelines of farmers who have seasonal workers arriving at different times of year.

Ken Forth is an Ontario broccoli grower who is also president of FARMS, the non-profit organization that administers the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SWAP) in Ontario. About 18,000 workers are expected to be placed at about 1,150 Ontario farms this growing season, he says.

SWAP, established in 1966 to respond to a shortage of domestic agricultural workers, is considered a successful program that works not only for Canadian farmers, but is important to the home countries of the seasonal workers who come to Canada.

Forth strongly believes the hands-on oversight, the involvement of several agencies and federal officials, and an annual review with all countries involved ensure seasonal workers are treated fairly, whether the issues are labour-related or living conditions. They are guaranteed all the benefits that Canadian workers receive, including WSIB, some EI benefits, and CPP — all the rights that any Canadian agricultural worker would receive, he says.

Farms employing seasonal workers are subject to random integrity audits, he adds, which would bring to light any irregularities — he has had several audits over his years as a grower.

“Our program has been successful for so long because it provides benefits to everyone who participates in it — from the growers who need supplemental seasonal labour, to Ontarians who are able to buy top-quality local foods at the grocery store, and the workers themselves who are able to improve the quality of life of their families at home,” says Forth.

He says he knows of many seasonal workers who have put in their years in Canada, reached the age where they want to retire, and are collecting CPP in their home country. EI offers some benefits, although not for the months farmworkers are at home — they sign a seasonal contract. They do get paid if they are injured, he says, and receive health insurance as soon as they land in Canada. “They have exactly the same rights as all Canadians. They also have the same coverage for health care.”

And as someone who ran the agricultural program with WSIB, he says, seasonal workers are treated the same as anyone else.

As for living conditions, he says he’s been having seasonal workers on the family farm for 53 years, “and we’ve been inspected 53 times in 53 years.”

Over the decades of the program, guidelines, like living conditions, have evolved, says Forth. “Most of the farmers have done a heck of a good job. We wouldn’t get passed if we weren’t doing a good job. Inspectors wouldn’t sign off.” So how do farmers continue to get a bad rap? Forth is exasperated with the criticism, and exhausted trying to defend farmers. Hudgin says he wishes he knew the answer to that. Public health units across Ontario all have the same guidelines to follow for their safety inspections, and he knows his inspectors follow them to the letter. He speculates that maybe some public health departments with larger farms in their areas, thus more workers and more housing to inspect, might be short on resources, but he’s worked in different areas and not seen evidence of that, he says.

Niagara has about 3,000 seasonal workers and about 500 housing units to be inspected. Farms are typically smaller, and living conditions are good, more likely to be in houses than large dormitory-style bunkhouses, says Hudgin. The last update to guidelines was made in 2010, and with current standards, he says, he can’t understand why workers are still experiencing some of the issues that are reported in the press.

“I’m not aware we have those things going on here. Our operations are pretty good, they provide good housing. I can’t say what’s happening in other communities.”

In Niagara, though, he’s been “quite impressed” by what he’s seen. “We have a good program, we have good farmers and good conditions. Some farmers get the same workers to come back every year, and they treat them like family. In essence they have the same rights as any resident in Niagara.”

But Hudgin adds, “we can’t control how a farmer treats his workers. I don’t know how you control that.”

He mentions Quest as a resource for workers. It is an organization made up of a group of partners who came together to provide accessible, high quality care for seasonal workers in Niagara, including health care services and promotion, developed in collaboration with local community stakeholders. Services are currently delivered across the region, including Virgil, and through farm visits.

Hudgin says if workers have specific complaints or concerns, there are signs in different languages posted in their housing, “with numbers to call if there are any concerns about their work or living environment.”

Public health departments have had the responsibility of inspecting housing “for many, many years. There was an update in 2010, but we’ve been doing these housing inspections a long time.”

Although few complaints come directly to public health, he adds, “if we see something that falls into the category of safety, such as a rodent infestation, we can issue a section 13 order under public health protection.”

Forth says of the complaints he hears, if there are farmers who don’t treat their workers well, “there are damn few. And if there is any truth in it, I don’t know where it is.”

Activists for farmworkers are hesitant to speak out about specifics, as are the workers, for fear of retribution, or of hindering their efforts to help. They stress not all farmers are being painted by the same brush, and that the existence of a few “bad actors” is not the issue — the problem is a system that allows them to continue, unhindered and unaccountable. One seasonal worker at the rally and march through Virgil recently was willing to speak about a farm with horrific conditions — not in Niagara — and although he is not at that farm this year, he is worried about friends who are.

Of great concern for them is getting hurt — many farmworkers know someone who has been injured by farm equipment, and has experienced an eight-week delay, with no financial support for themselves or their families, until EI kicks in eight weeks later.

There are also instances of workers permanently injured, cut off from WSIB, unable to afford the treatment they need at home or to care for their families.

Jane Andres writes of one such worker for this week’s Local. She has chronicled his situation in the past, but she is concerned he is getting worse.

“Over the past 17 years I have personally met men who have been injured, yet did not receive compensation or adequate treatment for their injuries,” says Andres.

“There are many farmworkers who know of people in their communities back home who can verify that it still happens. There has been much improvement in the health care and response to injuries in the past few years due to growing public awareness, but there are still people who fall through the cracks. It gets even more complicated when WSIB rewards employers who report fewer accidents. As a result a few employers have put more pressure on their workers to not report it as a work-related injury.”

There is no doubt, all agree, the seasonal workers program is good for all of us, our food supply, our farmers and the temporary workers who come to work on Canadian farms. But they also agree it’s not perfect — and if the workers and those who help them are afraid to speak out with specifics, if all the safeguards in place can’t protect them, if the farmers won’t police each other, how will it change?