The game of lacrosse has a long history amongst Canada’s Indigenous peoples, including in Niagara-on-the-Lake, and a group of lacrosse coaches and players from Fort Erie are working hard to keep that history alive.

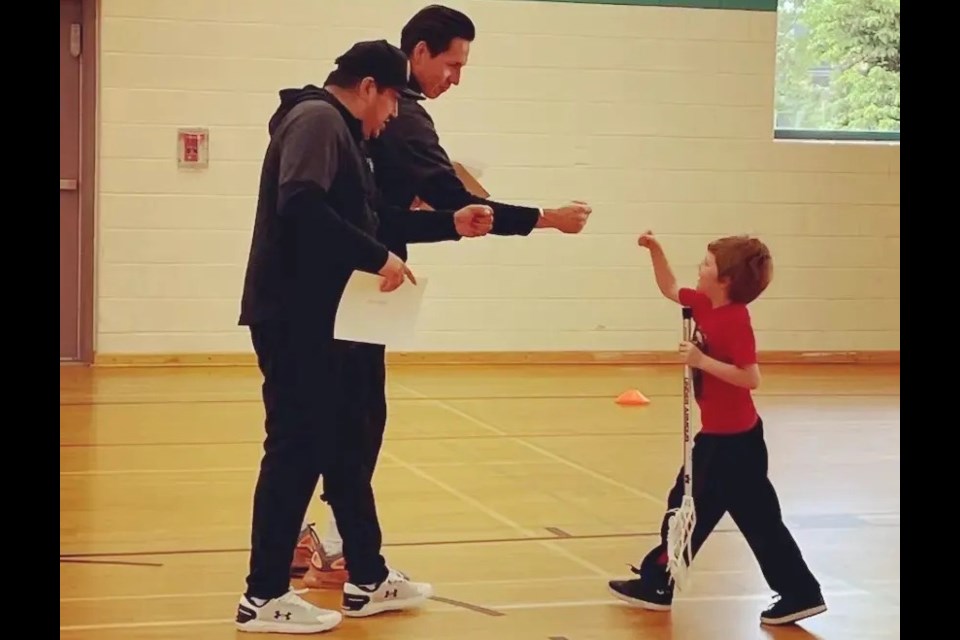

Jace Sowden and his partners Cassidy Doxtator and Blue Hill are the principles behind FUSE Lacrosse. They specialize in building essential skills, fundamentals, conditioning, agility and speed to help lacrosse players reach their goals in the game.

But just as important to the trio is that they build an understanding of the traditional teachings of lacrosse and its roots from the Haudenosaunee perspective as the Creator’s game. They do this via special sessions on the history and culture of the Indigenous game.

To explain the importance of lacrosse and its teachings, Sowden says he was just three years old when he began to play the game competitively. But his introduction came even earlier than that. As he explains, Haudenosaunee tradition is such that when a boy is born, a lacrosse stick is given at birth.

“My family has upheld that tradition,” Sowden says. “I have two boys myself (three-year-old Cree and four-month-old Lake), and my brothers gifted them lacrosse sticks either the day before or the day after they were born.”

Though most modern day lacrosse sticks are made with a composite material, those traditional sticks were made of wood, often hickory. The spirit of the tree is believed to connect the player to Mother Earth as they play for the Creator.

“Our youth initiative started really organically,” Sowden tells The Local. “We started offering these sessions in Fort Erie about four years ago, just to revive the interest in lacrosse and encourage people to be active. As we learned more about the game, though, we began to feel that it was our responsibility to do this.”

Sowden is Houdenosaunee, with roots in the Cattaraugus-Allegany reservation in upstate New York. He, Doxtator and Hill, all with a Houdenosaunee background, grew up in the Niagara region, and identify themselves as urban Indigenous people.

“What lacrosse has done for us,” Sowden says, “is given us that tradition component. Our families were an intricate part of teaching us the values of the game. Although we all lived off the reservation, it gave us a connection back to our home communities. It really helped to shape our identities.”

The Onondaga and Haudenosaunee Nations believe that one of the gifts the Creator can bestow on any individual is the gift of sport. Traditionally, the Onondaga and the Haudenosaunee called the game Dehoñtjihgwa’és, roughly translated to mean, “they bump hips.” That’s certainly an apt description for an activity that happens often in a lacrosse game.

It is believed the Haudenosaunee played the game as early as 1100. In its purest form, lacrosse was played by tribal warriors for training, recreation and religious reasons outside on a field, often with no boundaries, and with no official limit on time.

French Jesuit missionaries in the 1630s came across games of lacrosse being played by the tribes in the St. Lawrence Valley. One of them, Jean de Brébeuf, wrote about the game being played by the Huron Indians in 1636 and it was he who first referred to it as lacrosse.

“It’s really rooted in the fabric of the Haudenosaunee people and Iroquois Confederacy,” Sowden says. “The values in the teachings that are involved, including respect, mutual understanding, mindfulness and the strong bond that you get from playing are the values of our people.”

Niagara’s physical proximity to those early days of the game has made the region a hotbed for the modern day version of lacrosse.

“Think of it at the professional level,” says Sowden. “The Premier Lacrosse League (PLL) and the National Lacrosse League (NLL), a lot of the people in those leagues come from Niagara. A huge number from St. Catharines, and there’s some from Welland, Fort Erie, Buffalo and upstate New York.”

Niagara-on-the-Lake is part of that lacrosse hotbed as well.

Andy Boldt, coach of the NOTL Thunderhawks U22 team this year, says in the past, most NOTL lacrosse divisions were composed of about 40 per cent indigenous players coming from Tuscarora Nation in New York.

He mentions players such as Rich and Travis Kilgour who played in NOTL. They went on to play for the St. Catharines Junior A Athletics and with the NLL’s Buffalo Bandits. Both have their numbers retired and are in the hall of fame.

There’s also Ron Henry, who coached in the NLL, the Arena Lacrosse League (ALL) and for the Tuscarora Senior B team as well as in NOTL, and his brother Don who played for the Bandits in the 1990s. NLL player Jim Bissel came through the NOTL program, as did Randy and Roger Chrysler.

Randy Chrysler is a long-time coach with the now-defunct Niagara Thunderhawks Junior B team. Currently the defensive coach for the NLL’s Buffalo Bandits, Chrysler’s resume includes stints on the bench for the 2014 Iroquois Men’s box lacrosse team, the Six Nations Arrows and the Tonawanda Braves Senior B team.

Chrysler is one of many Indigenous people from New York state who have contributed to lacrosse in NOTL.

“My dad coached there, I coached there, my son coached and played there, and my grandson is now playing there,” he says. “Four generations. It’s like our first home, actually.”

Chrysler remembers playing as a five-year-old on the same Tuscarora team as kids as old as 17. That was because Tuscarora’s minor lacrosse program had begun to fall apart as their box, or arena, got old and became too expensive to repair. As even that team was beginning to fall by the wayside, his father contacted NOTL Lacrosse and signed Randy up to play here.

“He would go get a van, and he’d pick up half the players in Tuscarora, kids from our territory and around the area, and we’d come up to play,” Chrysler laughs. “We got there, and it was just like family. The friendships we made in Niagara-on-the-Lake are lifetime ones.”

Playing alongside non-Indigenous teammates had its advantages, too. Many of those friendships he speaks of were formed over the sport, but also bridged the gap between cultures, creating a true understanding of each other’s lives.

With difficulties at the border since March, 2020, NOTL lacrosse has seen a decline in registration, as well as a decline in the number of American players coming across to play. That, of course, includes many Indigenous players, who have looked elsewhere to pursue their love of the game.

In light of that, Chrysler’s proudest accomplishment to date might be his current role as president and head coach of the newly formed Tuscarora Tomahawks of the First Nations Junior B Lacrosse League.

“It’s the first time in Tuscarora history that we have had a Junior B program,” states Chrysler. “It’s because of the border, and COVID. Just to see our community back together, and our minor system being re-formed. It’s amazing.”

Like Chrysler, Sowden is also giving back to the game. In his case, it’s through FUSE Lacrosse’s skills sessions and its lessons on the game’s culture and history, three of which were run recently as part of the Niagara Folk Arts Festival.

Those cultural lessons include a focus on the values of tradition, respect, leadership, perseverance and integrity. FUSE uses active discussions to create an environment that encourages conversation and builds understanding of Indigenous history while growing the game of lacrosse.

“We use our Haudenosaunee perspective to give back to our community,” Sowden says. “One of the biggest things we recognize is what lacrosse did for us as people. It’s so important to help youth to identify themselves and find a purpose.”

And it’s an opportunity for the three men to create a community around the game, and to move toward healing in a time of truth and reconciliation.

“It’s a chance for dialogue,” he says. “It’s an opportunity for discussion in light of the finding of all the unmarked graves. We can share knowledge, not only about the game itself, but also about some of the challenges Indigenous people face. We can have those meaningful discussions while doing something active, and surrounding ourselves with like-minded people.”