An outbreak of avian influenza last week in West Lincoln has Niagara poultry and egg farmers on high alert.

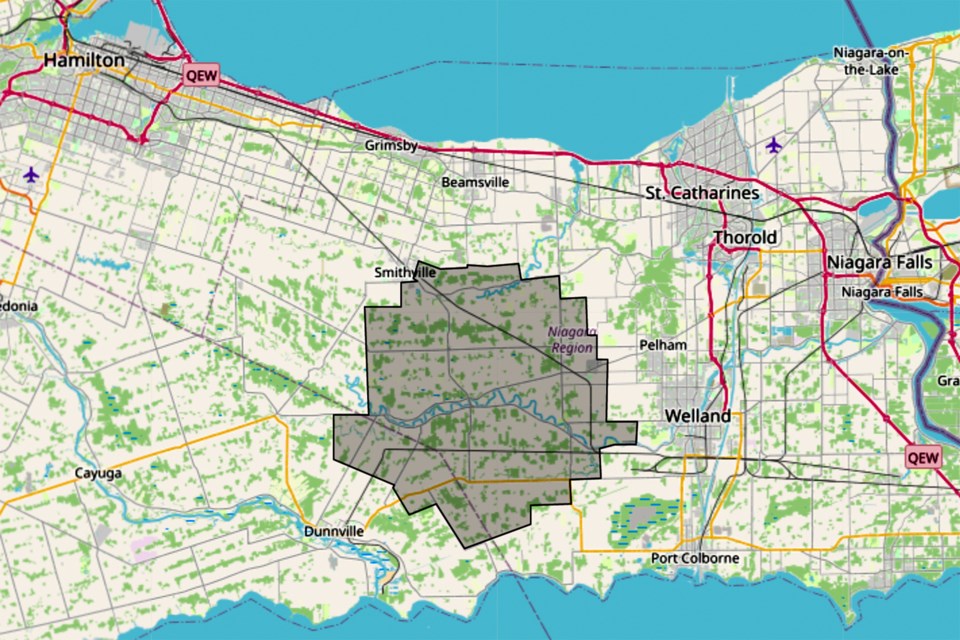

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), which is empowered to oversee such outbreaks, has established a ten-kilometre “primary control zone” that surrounds the farm where the infection was reported.

Avian influenza, also referred to as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), occurs each spring when migratory birds — primarily waterfowl like Canada Geese — return from the south, carrying infection with them. The particular strain of avian flu currently circulating is highly contagious, and lethal to birds.

In 2022, a number of explosive outbreaks of the H5N1 avian virus hit poultry populations worldwide, with 270 Canadian farms, and almost five million domestic birds, affected.

CBC News recently reported that the avian virus is spreading to mammal populations, prompting concerns about the increased potential for transmission to humans. A recent outbreak of H5N1 at a Spanish mink farm led to the culling of the entire population of more than 50,000 animals.

Some researchers have warned that the virus can evolve to infect humans and potentially start a future pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) has documented almost 250 human cases of H5N1 avian influenza in China, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam in the past 20 years, involving people having direct contact with infected birds. In half the cases, the individuals died.

Several H5N1 avian influenza vaccines have been produced over the years, but none are considered fully effective, given the mutating nature of the virus.

Niagara poultry farmers have received a communication from the Feather Board Command Centre (FBCC) regarding biosecurity and quarantine provisions. Signs of avian flu in birds include lack of energy and appetite, decreased egg production, swelling around the head, gasping for air, sneezing, lack of coordination, and sudden death. Bird owners are legally responsible to notify authorities of avian disease.

Backyard chickens, songbirds, and indoor pet birds could be at risk of catching bird flu when they have access to the outdoors. Infected wild birds can spread the disease by direct contact, or by contaminating the local environment, including ponds.

Rick Cavanaugh, the Niagara representative for Wallenstein Feed and Supply, which serves the poultry and egg industry, lives within the quarantine area that affects many parts of West Lincoln, Wainfleet, and Pelham.

“This is nothing to be taken lightly, since an outbreak in a non-commercial flock broke two days ago in Chatham–Kent,” he said. “I have seen how quickly a perfectly healthy flock under excellent management can become infected. Limiting travel and heightened biosecurity measures are paramount.”

Cavanaugh has worked in the poultry farming sector for close to 50 years. It was one of his customers in Wellandport that experienced the outbreak.

“[The outbreak] happened last Sunday,” said Cavanaugh, referring to March 12. “Poultry veterinarian Dr. Elizabeth Black was contacted when the farmer saw a sudden increase in bird mortality. There were no symptoms. These were beautiful turkeys ready to go to market. On Sunday, 17 birds died. On Monday, it was over 100. It’s very hard economically for the farmer and his family. Those birds are worth a lot of money. I have a lot of friends that are customers within the ten-kilometre zone that are very susceptible right now.”

Most people are not aware of the volume of poultry farming that occurs in West Niagara, said Cavanaugh.

“I have two families which are customers, both in West Lincoln, which together probably raise 300,000 birds. Many of the operations are second and third generation family businesses.”

Cavanaugh said that there is a humane protocol for euthanizing the infected birds, that involves carbon dioxide gas.

“It’s painless for the birds, they just go to sleep,” he said.

The wild bird population continues to concern Cavanaugh.

“I noticed last week some huge flocks of Canada Geese and Snow Geese passing through Niagara,” he said. “With the spring migration, it just seems like the population explodes. Geese, ducks, and raptors have been found to be infected with avian virus.”

Cavanaugh also is worried about the increase in urban and rural backyard chickens.

“The proliferation of backyard flocks has happened without the biosecurity and husbandry measures that commercial operations require,” he said. “I think if the Town of Pelham is going to allow backyard flocks, then they better be prepared to monitor the situation. What does the average person know about the proper care of any livestock, to keep them healthy? To the politicians within the Region of Niagara who are allowing or promoting backyard flocks, please reconsider. Those of us who work in poultry farming and own premises that have millions of dollars invested in biosecurity do not need any more health challenges added to the pressure of bird migration.”

The CFIA has provided the latest information on highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) detections across Canada on its website, located at https://inspection.canada.ca/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/avian-influenza/hpai-in-canada/status-of-ongoing-avian-influenza-response/eng/1640207916497/1640207916934.

The CFIA does not release details about the operations of individual farms, in order to help protect the privacy of producers.

Human infection is rare, but the Niagara Region Public Health has advised those who may have come in contact with potentially infected birds to self-monitor for avian flu symptoms, which include fever, cough, sore throat, aching muscles, vomiting, and diarrhea.