Tired about what they say is “cultural' and 'identity theft” by entities such as the Metis Nation of Ontario, two groups will meet in Winnipeg next week to discuss next steps.

Co-hosted by the Manitoba Métis Federation (MMF) and the Chiefs of Ontario, the two-day summit marks “an unprecedented gathering of First Nations, Inuit and Red River Métis leadership from across Canada, all of whom are united by concerns about the wholesale theft of their respective identities by those seeking to use them for their own purposes or gains.”

"We need to do this because governments and institutions are legitimizing groups making false claims in our territories," MMF senior official Will Goodon tells MidlandToday.

“They take money, jobs, opportunities away from Indigenous people. This issue is becoming more prominent."

Goodon points to an academic report that took a hard look at Ontario’s six recognized Métis communities, including Georgian Bay, and discovers that some of the MNO's Metis Verified Family Lines (MVFL) actually don't have a Métis root ancestor or forebear.

“The word voyageur, half-breed means Métis to them (MNO),” says Goodon, who notes it doesn't make sense Métis citizens would go east.

“The diaspora went west. No one went east,” he says. “Why would you go with soldiers who shot their families?"

Chiefs of Ontario Regional Chief Glen Hare says the event in Winnipeg will allow “legitimate rights-holders’ to address the federal government’s “deeply flawed” Bill C-53 legislation and highlight the need to protect Section 35 rights and “legitimate” Indigenous rights holders.

"We need to do this because governments and institutions are legitimizing groups making false claims in our territories,” Hare says.

MMF president David Chartrand has long been a vocal opponent of the MNO and led his federation out of the Métis National Council due to its decision to include groups like the MNO.

"Our warnings of Indigenous identity theft of the Red River Métis, First Nation and Inuit peoples are at the forefront in this country and the time has come for Canada to address these fraudsters and ensure they know who they are ‘treatying’ with," Chartrand says.

“We can no longer stand by and allow these cultural thieves and identity colonizers get away with the damage they are doing to our peoples.”

But MNO president Margaret Froh says there are legitimate Métis communities in Ontario and the two host groups are employing "revisionist history" and are concerned their slice of the funding pie will be diminished as groups like hers become stronger.

"It's a very different narrative they're sharing with the world," Froh says, noting Chartrand has praised the Powley decision in the past and his organization now wants to exclude Métis citizens from other locales.

"It's a 180-degree turnaround in (their) position. There's a long history of Métis communities across Ontario and the west. The only Métis community that's been (officially) recognized as a Métis community is the one in Sault Ste. Marie."

According to Froh, the MNO currently has about 28,000 members with "thousands in the Midland-Penetanguishene area" and receives annual funding from both levels of government to help run its $130-million operating budget.

Froh says the operating budget, which works out to $4,643 per citizen, allows the organization to offer members various health and social services along with financial incentives such as education bursaries and help for entrepreneurs.

"In the last five years, the growth has been relatively steady as we have more and more people who want to get involved," Froh says, noting the history of Métis in Ontario is one of a "forgotten" people.

"We've been left out of a lot of things. The funding is there because of the challenges we've faced."

While Goodon suggests people are now flocking to the MNO due to potential financial opportunities and for health reasons, given that Métis citizens in Ontario received COVID-19 vaccinations before the general population, Froh says she "can't say why someone becomes a citizen of any government" but knows citizens take pride in their ancestry.

Some time ago, Goodon’s group recruited University of Ottawa academics Darryl Leroux and Darren O’Toole to explore the provincial and federal government's decision to recognize six new historic Métis communities in Ontario, including Georgian Bay, in 2017.

And just last year, a political advocacy group representing 21 First Nations in Robinson Huron Treaty territory released a study co-authored by Leroux and McGill University's Celeste Pedri-Spade to disprove the historical existence of a Métis community in their broad catchment area.

"It’s our firm assessment – after reviewing thousands of pages of historical documentation meant to act as evidence for the MNO’s political claims – that the MNO has failed to demonstrate that there ever existed distinct 'historic Métis communities' anywhere in Robinson-Huron Treaty territory," they concluded.

For her part, Froh says the reports are nothing more than an extension of political agendas by those who seek to deny the Powley case and Métis existence in Ontario.

She says the organization stands behind its registry, which has undergone an independent, third-party review. Last year saw the MNO remove 5,000 citiizens due to incomplete membership applications.

"We've been very public and transparent with that," Froh says. "We have a registry that's incredibly solid. We have trained historians that run our registry."

Last year's report by Leroux and Pedri-Spade says that MNO’s “poor research practices have led it to make faulty conclusions about the historical existence of distinct ‘Métis’ communities in the Robinson-Huron Treaty territory.

“The MNO identifies historical actors as members of a distinct 'Métis' collectivity whenever the word 'breed' or the initial 'b' is used to record their identity, even when extensive evidence exists in the same or additional documentation that that individual was Anishinabek or a European/settler,” the report says.

“The MNO identifies an individual as 'Métis' even when that same individual is recorded as either First Nation or European much more often and over successive generations, which is counter to their own stated approach.”

The report goes on to note the MNO relies on historical documentation, normally secondary sources, that have proven unreliable in their identification of historical actors, when more reliable documentation opposes their interpretation.

“The MNO ignores recorded identities that were overwritten with an identity that challenges their own conclusions,” the report further states. “The MNO fails to verify its conclusions with multiple sources of documentation, usually because the historical record opposes their interpretation.

“The MNO actively omits historical data that calls into question their interpretation; we have recorded over 2,000 times that they engaged in such misleading practices during this study. The MNO even identifies some individuals as 'Métis' when they were never recorded as such in the extensive historical documentation they provide.”

The document also notes the MNO has failed to document the presence of an identifiable Métis community prior to Effective Control, a doctrine to identify the time when Europeans effectively established political and legal control in a particular area; that was a key component of the Powley decision.

“The majority of the individuals it has identified as ‘Métis’ are identified as such after Effective Control, in many cases several decades afterwards,” the report notes. 'The MNO makes these interpretive mistakes because its research is propelled by politics and not by sound research practices; it lacks the reliability and validity of peer-reviewed academic research.

"The MNO 'communities' do not meet the threshold of Effective Control essential to the Powley test and the overwhelming majority of their 'forebearers, Métis root ancestors,' and 'root ancestor descendants' were most often recorded as either Anishinabek or as white settlers. Had the MNO reported on the entirety of the historical record involving their VMFLs (Verified Métis Family Lines), their claims about 'historic Métis communities' would be exposed as false.

“Because of their poor research practices, the MNO has increased the size and scale of its communities by adding a remarkable number of VMFLs since the 2017 recognition announcement. This has the effect of increasing the number of Ontarians who are newly eligible for MNO membership and recognized as section 35 Aboriginal rights-holders.”

Goodon says these kinds of things have occurred because the MNO is set on increasing its membership.

But Froh says MNO citizens deserve anything they can get because of poor treatment in the past.

“The Métis were pushed off their land,” she says. “It’s a story of displacement, it’s a story of resistance, it’s a story of perseverance.

“You have families that should have had a leg up, that would now be old money, but they were pushed off their land.”

The MNO does not prescribe to a minimum blood quantum requirement, but “Métis rightsholders must have some proof of an ancestral connection to the historic Métis community whose collective rights they are exercising.”

Froh adds that “we believe that if your ancestors are Metis, then you are Metis.”

But Goodon questions that narrative.

“I think it’s a phenomenon you can probably trace back to 1982,” Goodon says of section 35 of the Constitution, which he notes was a great achievement of “our leadership at the time” since it marked the first time Inuit and Métis rights were enshrined in the Constitution.

“There’s this concept out there that mixed is Métis. Mixed is not Métis and Métis is not mixed,” Goodon says. “There’s a distinct way that Métis people became a nation.”

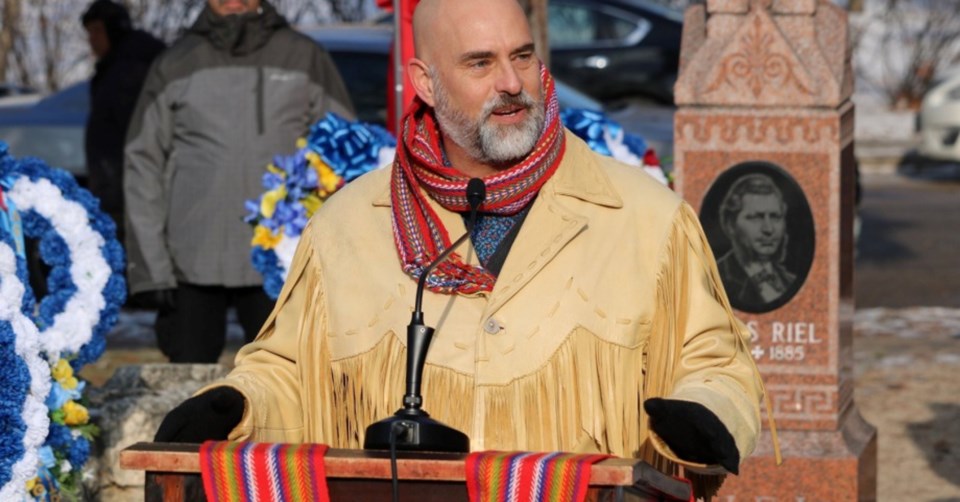

While Goodon says his organization has its own distinct heroes in people like Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont, its own traditions and culture and its own symbols such as the Infinity symbol, other organizations are hijacking these and calling them their own.

“All of these things happened in the west,” he says. “Kinship ties played this role where families intermarried.”

As an example, Goodon says that if he goes to visit Métis groups in Lac La Biche, Alberta or Regina, he’s going to come across people he’s related to.

“If I go out east, the same isn’t true; the same isn’t true for many MNO members. With the historic Métis Nation, it’s easy to see connections.”

Goodon acknowledges that MNO has done a good job of "political manoeuvering" over the years, including its work to have the Ontario government recognize six communities under the Métis umbrella in 2017.

“There were these new communities created by (former premier) Kathleen Wynne, MNO and (former federal cabinet minister) Carolyn Bennett,” he says. “There never were Métis before, but you get to COVID and these people are coming out of the woodwork so they can get the COVID shot, their kid can go to university and they can get a job with federal services," said Goodon.

“To me, there’s a lot of settler reconciliation guilt that plays into this what’s going on in Ontario,” Goodon says, pointing out that there’s almost “zero connection” between the “actual Red River” Métis and MNO members.

“I’m not saying that there weren’t intermarriages in Ontario, Quebec and eastern Canada, but when it happened with us this once-in-a-lifetime thing developed.”

Goodon says that unlike Ontario, for example, those in the Red River area flourished to create the Métis way of life through isolation when the French and Scottish fur traders went back to Quebec.

“Being ostracized a bit, this idea of nationhood slowly developed over time,” he says.

He also finds Froh’s views troubling since he says she’s determined that it’s OK for her group to recognize a person as Métis if they have some First Nations’ blood, but doesn’t believe someone in Quebec or the Maritimes should also then be considered Métis using the same parameters.

“That’s an extremely hypocritical thing for her to say. The test she uses would recognize Quebec Métis, Maritime Métis. Her arguments that she uses for herself would work in Quebec.”

According to Goodon, the MNO will create “this false ancestor,” making it sound like the classic George Constanza line that if you say something often enough, it has to be true.

“A lot of people won’t look behind the curtain to see what’s happening here. You (MNO) have been saying these things, but we don’t think it’s true. Yes, there were intermarriages, but that’s not what makes you part of the historic Métis collective. It’s an interesting tactic," said Goodon.

“We need to educate. Indigenous identity theft is becoming more recognizable as a problem. We’ve seen it with Buffy Sainte-Marie, Joseph Boyden…their last gasp is that they’re Métis.”

Goodon says the MNO employed researchers to try to find potential First Nations ancestors, voyageurs and halfbreeds and change them into Métis.

“It’s circular logic. They go back in time and forward in time. It’s really a strange phenomenon."