For more than 400 years, the Sanders family has passed down through the generations a portrait that comes with a story that sounds like legend: the oil on oak painting is believed to be the only likeness of William Shakespeare painted during his lifetime, making it an exceedingly rare and intriguing work.

For almost a century, members of the Sanders family, most recently Lloyd and Mary Gertrude Sullivan of Ottawa, have either flirted with or been focused on selling the piece, and have spent decades and considerable sums attempting to both authenticate it and find a suitable home. Sullivan, a Bell engineer in the Ottawa area before his retirement, inherited the painting from his mother in 1972—making him the latest in a long line of descendants to own the mysterious portrait, which crossed the Atlantic to Canada in 1919.

For much of the family, the portrait has never been just about money; it’s about recognition of their guardianship of this work and the contribution they have made to history and the global art canon. Lloyd Sullivan’s ultimate goal was to sell the “Sanders Portrait” to someone who would then turn around and donate the piece to a public gallery, where it could hang for all to see. So firm was Sullivan’s commitment that, in 2012, on the verge of having the work auctioned at Sotheby’s for an estimated millions of dollars, he called off the sale and headed home.

“It was precious to him on a different level,” says Alastair Summerlee, the former president of the University of Guelph, who was active in attempts to help find an interested buyer.

Lloyd Sullivan died in August 2019, and his wife, Mary Gertrude Sullivan, passed away the following spring. What they left behind resembles its own Shakespearean tragedy: a high-profile painting now in limbo, and a court battle over who should decide the next act. Earlier this year, an Ottawa judge rejected the arguments of one of Sullivan’s long-time friends and confidantes, who petitioned the court to have the estate trustee removed from the file because he couldn’t be trusted to secure a reasonable sum for the high-profile painting.

But more than money, this story is about value. If this work of art is indeed one of the only known portraits of William Shakespeare painted during his lifetime, what is it worth? What is the value of guardianship or advocacy on behalf of such a piece? And what is the value of friendship, of helping the Sullivans over the years with matters both personal and financial, when it comes to slicing up the fragments of a singular work of art?

“This is the only major asset Lloyd Sullivan had, and it is so important to Canada,” says Victor Weiner, an art appraiser in New York who has examined the portrait several times. “I don’t think the portrait has gotten its due. And he bankrupted himself to try to prove it. It's not that easy to move an extraordinary work of art.”

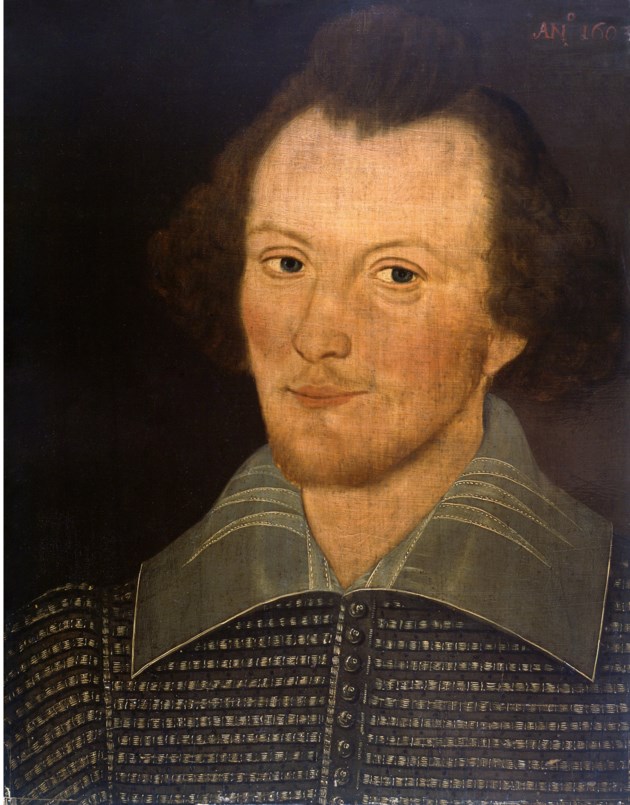

At 42 x 33 cm, the portrait is diminutive for such a significant work. Painted in muted tones, it depicts a middle-aged man in a black doublet, a smirk on his face and his hair a messy crown of curls. He bears a resemblance to the likeness of The Bard found in elementary and high school texts across the province. “The painting is in extraordinary condition,” says Wiener, noting that there is only one small area of damage. “It’s very rare to find a 400-year-old work this intact.”

On the back of the portrait, a label reads: “Shakspere; Born April 23, 1564; Died April 23-1616; Aged 52; This Likeness taken 1603; Age at that time 39 ys.” It is unclear whether the work was painted by a Sanders family member, or the Sanders simply came into possession of it shortly after its creation.

Over the last three decades, Lloyd Sullivan spent millions of dollars trying to have the work validated and appraised, with varying results. In general, the work has been favourably authenticated. At the University of Hamburg, dendrochronologists dated the oak canvas to 1595, and the wood was determined compatible with regional expectations. Scientists at the Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa validated the pigments as consistent with other early 17th century works. And radiocarbon dating at the University of Toronto found that the label on the back was indeed affixed within decades of the date on the portrait.

Determining the value of the work has been much more challenging. It has produced such wildly different estimates that the whole endeavour has the vibe of searching for buried treasure. In the least generous appraisal, based on the belief that the painting is indeed very old but not a depiction of Shakespeare, the price was set at US$100,000. But in the case of two separate appraisals obtained by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in 2016—both validating the Sanders narrative that the subject is indeed the world's most famous playwright—the estimates were US$8.5 million and US$50 million.

But like so many cursed lottery winners, the Sullivans’ jackpot turned into a liability. The push for authentication proved extremely expensive, and the Sullivans assumed more and more debt and services-in-kind, creating an expanding number of both individuals and businesses with a stake in the final sale price of the piece.

In 2002, members of the Sanders family signed a deed that recognized Lloyd Sullivan as the owner of the portrait but also established a framework to share the proceeds from any sale. Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP also claims to own a share worth $1-million related to the provision of legal services; that claim is supported by a Superior Court order mandating the portrait cannot be sold, transferred, moved, or encumbered without the law firm’s consent or a further court order. And other firms have staked out claims for the provision of professional services, including an accounting firm belonging to David Taylor, the current trustee of Mary Sullivan’s estate.

By the time of his death in August 2019 at age 86, Lloyd Sullivan had been seeking between $7-million and $10-million in exchange for the painting to settle his debts. It was that mounting debt load that set the stage for litigation.

Last summer, a friend of the family, Jim Meuse, petitioned the Superior Court of Justice in Ottawa to have Taylor removed as trustee on the grounds that he is either unable or unwilling to secure maximum value for the much-debated portrait. Like others, Meuse loaned money to the Sullivans, so he has a vested interest in any eventual sale.

Meuse has accused Taylor of a slew of malfeasance, from attempting to fetch a below-market price for the portrait to colluding with others to change Sullivan’s will, and he insists that he would make a superior estate trustee. “A good deal of Mr. Meuse’s argument on this application focussed on why he would be a better choice than Mr. Taylor as the trustee of Mrs. Sullivan’s estate,” wrote Justice Sally Gomery in her ruling. “This application, however, is not a beauty contest between the parties.”

In the factum he filed in court, Meuse outlines his longstanding friendship with the Sullivans and how they became indebted to him. The Sullivans and Meuse’s parents were friends, so he’s known them for decades. He says that in the late-1990s, Lloyd Sullivan asked him to become more involved with the project of finding a permanent home for the Sanders portrait. Meuse describes his involvement as both financial and one of moral support.

He claims he paid for the last scientific test on the painting, which involved the examination of ink used on the label. He claims he brokered a deal for Lloyd’s participation in a 2008 documentary, Battle of Wills, which chronicled their efforts to authenticate the work. And he claims he personally loaned Lloyd $10,000 in 2006, leading to the signing of an agreement that gave Meuse a two per cent stake in the gross selling price of the portrait. (Meuse admits that their financial affairs were somewhat messy).

Meuse portrays himself as a sort of saviour—a defender and provider for both the Sullivans and the portrait. In 2014, Meuse claims that Lloyd’s financial situation was so dire that he talked about giving the portrait to the first buyer who would offer him $500,000. Meuse says he worked to restructure the Sullivans’ debt, organizing the renovation and sale of their home and facilitating their 2015 move into Blackburn Lodge, a seniors residence in Gloucester, Ont., just outside Ottawa.

His contributions weren’t simply financial, he insists. In his court filings, Meuse says he ferried the Sullivans to appointments, took them for meals, picked up prescriptions, and liaised with Blackburn Lodge to ensure they were well taken care of. Near the end of their lives, Meuse says he arranged for the devout Catholics to have last rites performed. When they passed away, he says it was left to him to arrange their cremations, funeral services and burial plots. Meuse even arranged for Mary’s funeral, in the early days of COVID, to be livestreamed. “Jim always acted with care and compassion in these matters, and with complete transparency,” notes the factum.

But while Meuse describes himself as a paragon of altruism, decency, and friendship, he paints a remarkably unflattering portrait of Taylor. In his factum, he makes several salacious allegations, including accusing Taylor of trying to change Lloyd’s will, via competency hearing and through the presentation of false or misleading information, to remove three Catholic charities as beneficiaries. He also claims Taylor did nothing about a bank account in Mary Sullivan’s name that appeared to be conducting several fraudulent transactions, and accuses Taylor of being involved in a fishy undertaking to transfer ownership of the portrait out of the Sullivan estate.

Meuse also underscores Taylor’s lack of expertise in Elizabethan art, suggesting such qualifications are essential for obtaining a maximum sale price for the portrait. He suggests that Taylor has partnered with any number of people either deleterious or clueless. Daniel Fischlin, Professor in the School of English and Theatre Studies at the University of Guelph, as well as Founder and Director of the Canadian Adaptations of Shakespeare Project, has long been involved with the Sanders portrait; Meuse now accuses him of trying to “hold the estate ransom” by withholding certain materials that might be required in a prospective sale. (Fischlin, who was also a close friend of the Sullivans, declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Meuse also faults Taylor’s partnership with an Ottawa-based appraiser who runs a small antique and fine art business. The appraiser is dismissed by Meuse as a small-potatoes dilettante, in over her head and overcharging the estate in her attempts to engage auction houses he deems completely inappropriate partners for the sale of the portrait. In one example, Meuse cites a recent approach to Christie’s as “clear evidence of incompetence.” The auction house requested the portrait be shipped to London for further authentication, something he deemed unnecessary and cost prohibitive.

Meuse seems particularly fixated on the Wiener appraisal for US$50 million. It is, by far, the highest estimate of the portrait’s value. If sold for that amount, Meuse’s two per cent stake would be worth US$1-million. “The Sanders Portrait should be treated as possibly the most important piece of trophy art to come to market in many years,” notes the factum. “The important dealers and auction houses should be competing with each other to represent the Sanders Portrait.”

The case spent several months winding its way through the court system, and when Justice Gomery’s judgment was released in early March, it was scathing. Over and over, Meuse appears to have made inflammatory and largely unfounded claims without the understanding that if he petitioned the court on these grounds, they would be subject to scrutiny.

Justice Gomery paints her own portrait—that of a man grasping at straws to exercise control over a cultural item he has optimistically tied to his financial destiny. She dismissed all his arguments, suggesting there was little proof that Taylor was acting in any way inappropriately or negligently as trustee. She noted that Taylor has accomplished a lot in a relatively short period of time, adding that “he may well have accomplished more but for the necessity of defending this application.”

Much of the case law Justice Gomery cited was relevant to the role of trustee, and the importance of honouring the wishes of the dead when it comes to the execution of an estate. James Cook, a lawyer with Gardiner Cook in Toronto who has been following this case, says he was fascinated by the fact Meuse attempted to appoint himself trustee based on a personal assessment that he could simply do a better job. “I found it kind of a remarkable premise because courts are generally quite deferential to the testators and the will as to who they wanted to be the estate trustee,” Cook says.

For all of Meuse’s insistence of his closeness with the Sullivans, situating himself somewhere between a son and a fixer, Justice Gomery found it noteworthy that the couple did not appoint him to manage their affairs after their deaths. She noted that removal of an estate trustee should only occur “on the clearest of evidence that there is no other course to follow.” Not only did she deny Meuse’s application, she also ordered him to pay Taylor’s legal costs in the amount of $40,000.

Taylor has indicated that he will pursue all possible avenues to a reasonable sale, including selling the painting outside of Canada, but the final chapter of this story has yet to be written. For his part, Meuse says there has been no movement on attempts to sell the portrait, which, according to the court ruling, remains in storage at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Meuse is also adamant that his legal action was motivated by nothing more than a desire to see the Sullivans’ final requests fulfilled. “I would like to see the painting sold in a timely manner for a reasonable price and for credit to be paid out to the beneficiaries, because that’s what Lloyd and Mary’s wishes really were,” Meuse said in an interview. “I looked out for their finances for five years and got them straightened out and never charged one nickel for that. I just did it because I loved Lloyd and Mary.”

There’s an inescapable sense of tragedy associated with this portrait and Lloyd Sullivan’s single-minded but unsuccessful efforts to find the appropriate buyer and facilitate a permanent home. He was, as might be imagined, highly protective of the portrait that made its way across the ocean and was once tucked in brown paper and kept under his grandmother’s bed. “The portrait is part of Canada’s immigration story,” says Wiener. “I’m frustrated this hasn’t moved forward. Maybe it’s even moved backwards because Lloyd is dead.”

Summerlee says that, in a bitter irony, it was Lloyd’s very expensive attempts to authenticate the portrait that set the stage for today’s complicated legal jousting and diminished the likelihood that his ultimate wish will be fulfilled. “Getting a deal from somebody who has disposable wealth and who has a reputation, the last thing that they want is to be involved in something that may end up a huge legal battle at the end of the day,” Summerlee says.

For the Sullivans, up to their eyeballs in debt, the money had always been secondary to fit and legacy, to legitimizing and then revealing this gem of a painting to the world, ideally through a Canadian institution. Throughout his lifetime, Sullivan somehow avoided the common trap of conflating value with money. In 2013, close to another deal that was ultimately scuttled, Lloyd told The Globe and Mail that such an arrangement would be great not just for him, but for Canada.

“What do we have?” he asked. “Maple syrup? The beaver? The flag? The Toronto Maple Leafs? This is terrific.”

Sarah Treleaven is a journalist in Nova Scotia. Her writing has appeared in Harper's, Report on Business magazine and Maclean's.