We are eating the clothes we wear. The portions are microscopic—tiny synthetic and natural fibres released from textiles called microfibres—but they are prevalent, prolific even.

Many of these microfibres are plastic, contributing to the global problem of human exposure to microplastics. A 2021 study estimated the average child and adult ingests 883 particles of microplastic per day, and that doesn’t include the natural fibres.

Microfibres are released into water and air daily and have been accumulating since the 1950s, when synthetic clothing was first introduced. Numbering in the trillions, these minuscule particles float in lakes, rivers, waterways, and even airstreams. Dyed and otherwise chemically treated microfibres have made their way to the top of Mount Everest and to the icy landscapes of Antarctica.

A 2019 study found microfibres in more than 90 per cent of rainwater samples taken from across Colorado, including some from 3,000 metres up in the Rocky Mountains. They’re in the Great Lakes, in the digestive systems and organs of wildlife, and recently they’ve been discovered in human blood, lungs and digestive systems.

The macro issue of microfibres is being tackled in two small Ontario towns, where ongoing research has global significance. Volunteers from Collingwood and Parry Sound who have been catching and collecting debris from their washing machines are contributing to a science experiment that may help alter Canadian laws to protect water quality.

It’s through this research that washing machines have emerged as a key gateway to stem the microfibre tide.

One of the biggest contributors to microfibre pollution in water is the effluent from washing machines, which is why the environmental science-focused charity, Georgian Bay Forever, is supporting research that uses filters to catch those microfibres when they are released during a load of wash.

David Sweetnam, executive director of Georgian Bay Forever, said the best option for dealing with microfibre pollution is prevention. The charity has supported research into microfibre filters for washing machines and is advocating for mass-scale use of filters to capture microfibres that come from clothing before they ever enter the water treatment system. “The approach is very much more ‘let’s keep them out’ rather than ‘get them out after the fact,’ ” said Sweetnam.

A study undertaken by Georgian Bay Forever and University of Toronto Rochman Lab, has proved that microfibre filters do work to significantly decrease the ongoing flow of the environmental pollutants.

Lisa Erdle, who was part of the team at the Rochman Lab working on the washing machine filter project while she was completing her PhD, said microfibres are the most common contaminants in the Great Lakes and around the world. “Studies have shown they can cause negative effects, both the synthetic and natural fibres,” Erdle said. “But there is something we can do about it.”

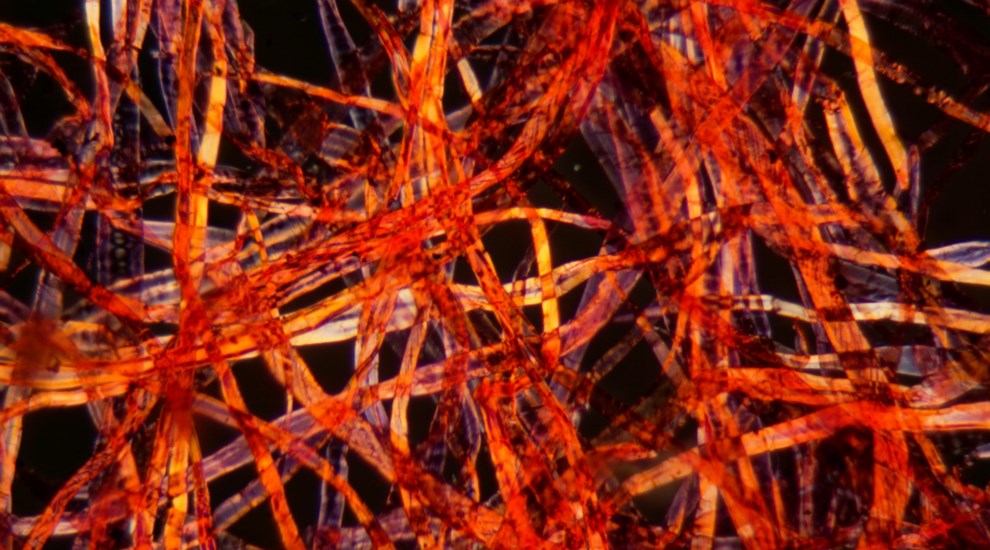

Microfibres are anthropogenic (environmental pollutant) fibres less than five millimetres long. They come from clothing and textiles made from synthetic materials like polyester, nylon, or spandex, and also from natural, chemically treated fibres such as cotton or wool. Though not all microfibres are plastic, deep dives into the debris show they are mostly microplastics.

Microfibres can be as small as three microns. For comparison, a human hair is between 50 and 100 microns.

The fibres contaminate habitats and wildlife, and studies published this year have found microfibres in human blood samples and deep inside human lungs. A research paper published in the Netherlands in March, for example, discovered polymers from plastics in whole human blood from 22 healthy blood donors. While this study demonstrated that plastic particles can enter the human bloodstream, the authors say more research is needed to understand whether plastic particle exposure is a public health risk.

“The research being done on health effects in humans only really started 1½ years ago, and not a lot is published yet,” said Sweetnam. “We’re on a bit of a threshold here.”

Another study from the University of Hull in England, also published in March, detected microplastics in all regions of human lungs, indicating that humans can be exposed to microplastics through inhalation.

Erdle, who completed her PhD studying microfibres in the freshwater food web, said this study was especially interesting because it found microfibres were the most common particle type in human lungs. “There were cellulose fibres—that were clearly not natural because they were dyed—in human lungs,” Erdle said.

A 2017 study out of Spain estimated 4.8 million tons of synthetic microfibres have entered water bodies and soil since 1950. That number doesn’t include the natural fibres also entering water and soil.

There are two ways microfibres can be environmental pollutants, Sweetnam explained.

They are physically harmful as a “mechanical object.” Creatures from micro-organisms to fish will ingest microfibres, become full and unable to digest the fibres—then starve to death while feeling full. They can also become malnourished, delaying the emergence of micro-organisms at the base of the food web.

If timing in one part of the food web falls out of sync, the effects ripple to other parts of the web by disrupting food sources at key growth stages. Fish that have just hatched, for example, may not be able to find their main food source because of delays in those micro-organisms emerging.

In a webinar presentation, Georgian Bay Forever co-ordinator Brooke Harrison said researchers who sampled lake species of fish (yellow perch, brown bullhead, white sucker, and shiners) found microplastics in 100 per cent of the samples. Nearly all of those microplastics—96.9 per cent—were microfibres. The researchers further found up to 915 fibre particles per fish.

The second way microfibres can be harmful is as chemical vectors. Most, if not all, fabrics are treated, whether natural or synthetic. A couch, for example, is treated with stain-resistant chemicals and wool is treated to withstand washing. The fibres can also absorb chemicals from the water or environment. “They basically act as sponges, absorb the chemicals, and, if they’re ingested, those chemicals can be released into tissues,” said Sweetnam.

There are no natural mechanisms or enzymes for breaking down or digesting microfibres, which are impregnable. “The fibres we’re talking about are unusual, and not natural,” said Sweetnam. “The eco-system hasn’t evolved in any way to be able to break them down.”

Microplastics are found in all kinds of food, from beer, salt, and drinking water to tea and meat. “We are eating plastic,” said Erdle. “We’ve also seen a lot of microplastics and fibres getting into our food from the air.”

Erdle said she has seen studies showing that microfibres can settle on dinner plates after they are placed on a dining room table. “There’s a pigpen effect of microfibres all around us,” she said. “We’re literally eating our clothing.”

By studying wildlife, scientists have reported adverse effects of microfibres impacting survival, growth, feeding behaviour, reproduction, and the hepatosomatic index (ratio of liver to the rest of the body size). “We’re still learning what the effects are to people,” Erdle said. “But I think we know enough to act even before we have all the answers to questions on impact to human health.”

Georgian Bay Forever has focused its research and education on washing machines, hoping to close that floodgate and stop the constant flow of microfibres into wastewater systems. A massive number of microfibres is released in the laundering process: between 200,000 and 2.7 million particles per household, per week, according to the Rochman Lab/Georgian Bay Forever research.

Wastewater treatment plants are catching many of the microfibres that go through the pipes, though it’s not a perfect system. A filter designed to capture millions of microscopic particles would interfere with the process of treating wastewater in high volumes. “They process so much water that having a fine mesh filter to catch microfibres would slow down the process too much,” said Erdle. “They would clog up very quickly.”

She said treatment plants do capture about 95 to 99 per cent of microfibres in the sludge they produce, but in Ontario and parts of the U.S., that sludge is spread as fertilizer. Years later, microfibres can be found where the fertilizer is spread, ending up in stormwater run-off and eventually back into the water system.

If a wastewater system is overwhelmed during a storm event like the Collingwood, Ont., facility was in September 2021 and untreated sewage is dumped into Georgian Bay, so are millions of microfibre particles. “We have this impression that the Great Lakes are pristine water bodies,” said Sweetnam. “What we really need to talk about is the fact that we are using them as a sewer. And we need to stop thinking about them in that way or they won’t be pristine for long.”

Studies on water samples from Lake Superior, Huron, and Erie conducted in 2013 showed 43,000 particles of microplastics per square kilometre. In 2014, samples from Lakes Erie and Ontario and the rivers feeding into them showed between 90,000 and 6.7 million particles per square kilometre.

“It’s never too late,” said Sweetnam. “We need to stop doing the damage…We’re in that position in the Great Lakes where we still have amazing water quality. The more crap we throw in it, the more expensive it’s going to be to clean that out to get drinking water.”

Georgian Bay Forever worked with the University of Toronto Rochman Lab to test a theory: Would adding a filter on a washing machine prevent microfibres from ever entering the wastewater system and, as a result, prevent them from getting into the ecosystem?

Their theory proved correct. In a lab setting, filters worked to reduce the number of microfibres in washing machine effluent by between 87 and 89 per cent.

Applying it to a real-life situation, the team led a community-scale pilot experiment in Parry Sound, Ont. Erdle, who now works for one of the study’s co-authors, the 5 Gyres Institute in California, said the pilot project was important because it showed washing machine filters work in a community setting. She said Parry Sound was a “Goldilocks” community because it was big enough to have a municipal wastewater system, but small enough that 100 filters could produce a measurable impact.

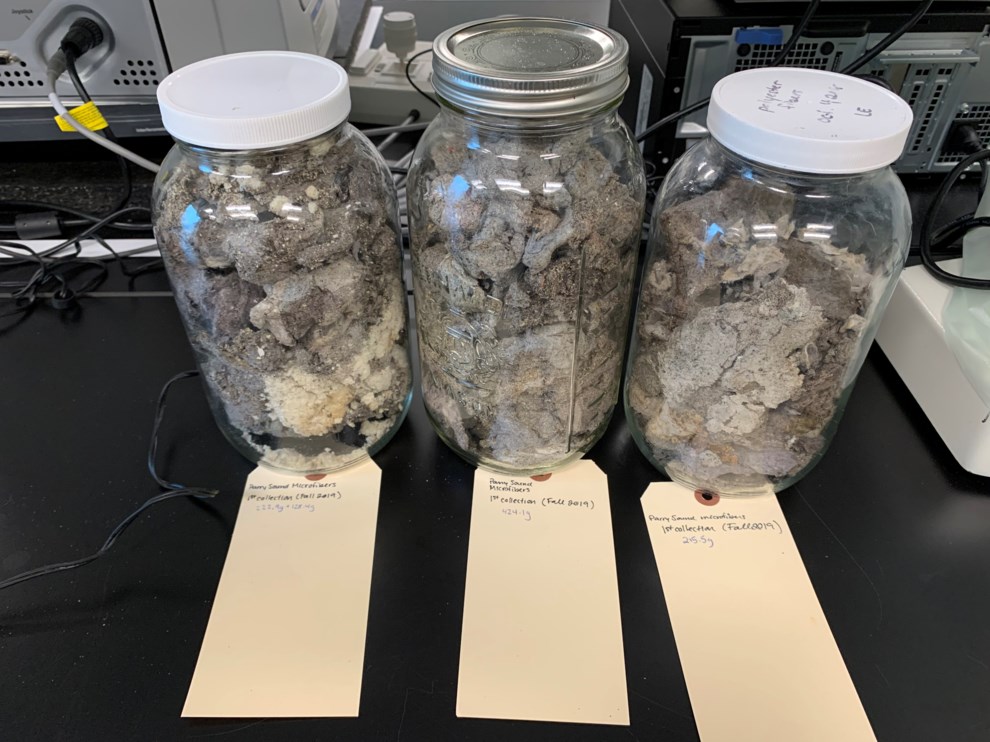

The team installed 97 Filtrol brand filters, made by Minnesota-based Wexco, in homes connected to the municipal wastewater system, which represented about 10 per cent of households in Parry Sound. The research team collected wastewater samples during the two-year pilot project. People with washing machine filters in their homes were asked to collect and save the lint captured, which the team also analyzed and measured.

Wastewater testing showed an average decrease of 41 per cent in microfibers in the effluent after filters were installed, even though only 10 per cent of the homes received filters. “The extra reduction is quite interesting," said Sweetnam.

Like all good scientists, Sweetnam has a hypothesis for that reduction: as the team sought volunteers to have filters installed, the public awareness may have inspired people to take other actions to reduce their microfibre emissions. Behavioural changes such as laundering less, buying used clothing, adding a fibre collector to the inside of the washing machine, and washing with cold water can reduce the number of microfibres that end up in household wastewater. “We were quite thrilled to see that kind of impact,” Sweetnam said.

Beyond the surprising extra diversion, the pilot project serves an important role as scientific evidence supporting microfibre filtration on washing machines. “It’s much better to say we need to put filters on washing machines because we can prove they will work [in real-life],” said Sweetnam. “That’s the real importance of the research we sponsored with the University of Toronto.”

Household filters in the Parry Sound project captured about 6.4 grams of lint each week, which is equal to between 200,000 and 2.7 million microfibres per week, depending on the household. Scaling up the data, the pilot project team estimated a filter on every washing machine in a city like Toronto would capture trillions of microfibres every year.

“We know that filters can capture most microfibres in a load of laundry, and they have a significant impact when we put them into households,” said Erdle. “There’s still an opportunity to turn off the tap of a significant source of microfibres, so it’s not too late.”

The latest pilot project by Georgian Bay Forever is currently underway in Collingwood, where the charity is installing 300 microfibre filters for free on washing machines in households connected to the municipal wastewater system. Those participating in the program have been asked to save the materials collected in the filter for study.

“We’re going to be keeping track of how much waste we’re diverting, and we can extrapolate that to the whole population of Collingwood,” said Sweetnam. “We’ll also be looking at and doing some experimentation on the types of microfibres to see if there are any major differences.”

.jpg;w=990;h=550;mode=crop)

While the pilot projects have involved installing after-market filters on household washing machines, those behind the experiments suggest the way forward is in the manufacturing of new washing machines. Although the filters can be added after-market, the efficacy varies, they can be pricey ($180-$220) and not all laundry rooms have space for installation. (The filters are about the size of a paper towel dispenser.) “I think it makes sense to install these into people’s homes,” said Erdle. “But I don’t think the burden should be on people to have to buy these filters. I think they should just be installed directly into these machines.”

.jpg;w=550)

Jessica Bell, who was elected as the member of provincial parliament for Toronto’s University-Rosedale riding in 2018, and is now running as the NDP incumbent in the current election campaign, pitched a private member’s bill twice in the Ontario Legislature. Both called for a law requiring all new washing machines sold in Ontario to have microfibre filters included at manufacturing. “The idea came from the community,” Bell said in an interview. “I thought it made a lot of sense. It’s a quick fix that will reduce microplastic pollution in our waterways.”

She liked the practical nature of the solution, viewing it as an inexpensive and effective part of a comprehensive strategy to protect waterways from pollution. Her last private member’s bill was introduced on March 22, but the Ontario government was dissolved for the June 2 election before the bill had a chance to pass. “The government of the day has the power to introduce this legislation and make it law any day they want,” said Bell.

She said it was citizen advocacy that first alerted her to the issue of microfibres spewing from washing machine effluent and ending up in waterways. “This is how it happens: people stepped up, they tested it themselves, they found the technology and now they’re working with legislators to introduce the legislation,” said Bell. “We’re building a movement to protect our waterways and get microplastic pollution out of our waterways.”

Armed with the research to support microfibre filters, Georgian Bay Forever is also working with the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative (GLSLCI) and the Quebec-based environmental charity Le Grame to advocate for washing machine filters on a mass scale. As a bi-national coalition of mayors with a mission to protect and restore the Great Lakes, GLSLCI has access and clout in the rooms where provincial and national laws are made.

Phillipe Murphy-Rheaume, Canada Policy Director for GLSLCI, said the group is working to identify members of parliament who could introduce a similar bill to Bell’s, and also working with the University of Toronto to continue research on different ways to capture microfibres. “Research points to microfibres being the most prevalent form of microplastics in a lot of our bodies of water, and it’s certainly an area we want to tackle and see some progress made on,” said Murphy-Rheaume. “It’s one of the many issues we’ve been monitoring, and, thanks to the leadership of Georgian Bay Forever, it’s something that’s bubbled up a lot higher on our radar as an organization.”

He said he is ‘cautiously optimistic’ about future legislation being passed because of the simplicity and practicality of the solution. “Anything that puts the responsibility on the manufacturers to find a solution will be a lot more practical,” said Murphy-Rheaume.

Government involvement would also help create a “level playing field,” according to Sweetnam, who said legislation should include standards for filtration size and levels. Effectively, the government could establish a maximum level of microfibre particles allowed in effluent from washing machines. “For all intents and purposes, 100 per cent reduction is the goal,” said Sweetnam. “From a practical perspective, going from trillions to 100 or something like that is possible with a multi-tier approach.”

France has already passed a law requiring all washing machines sold in the country to have microfibre filters built-in by 2025. Murphy-Rheaume said getting similar legislation passed in Ontario, Quebec, Canada and the US will require ongoing efforts from not only lawmakers, but the public they represent. “The more the public is educated about this issue, the more they bring it up with their elected officials,” he said. “The more the elected officials become aware of this issue, I think it will build a groundswell that will lead to some quick wins.”

Microfibre pollution will not be erased by washing machine filters, nor will filters completely prevent fibres from ending up in washing machine effluent. Even if the filters are installed in new washing machines, old washing machines will continue to operate in people’s homes without filters.

“There are many ways these microfibres are getting into the ecosystem, and once you let them out it’s very difficult to remove trillions of tiny little microscopic particles. It’s impossible to remove those from the ecosystem once they get there,” said Sweetnam.

The filters also create a new problem: disposal of the wads of microfibres caught in them. The lint is currently tossed in the garbage, inevitably ending up in a landfill. “Throwing them into the garbage is imperfect,” said Erdle. “But it’s better than going directly into the water … Eventually there could be a future where we recover [and recycle] materials, we’re just not there yet.”

There’s also more work to be done to understand where airborne microfibres are coming from. “We’re trying to understand the pathways of microfibres,” said Erdle.

Now the director of science and innovation for 5 Gyres Institute, Erdle is currently working on a study to find out if clothes dryers are emitting microfibres into the air.

According to Sweetnam, the solution to microfibre pollution will need to be multi-faceted, involving filters on washing machines, standards for effluent, improvements to wastewater treatment plants, individual behaviours of the general public, and changes in the fashion/textile industry.

“Lots of thinking needs to be done at each of those levels,” he said. “It’s a pretty complicated system right now and there are lots of opportunities for innovation and improvement.”

For more information, or to find templates and information on how to send your government representative a letter supporting legislation to require microfibre filters on washing machines, visit the Georgian Bay Forever website.

Erika Engel is the Editor of CollingwoodToday.ca, a sister site of BurlingtonToday.com. An award-winning journalist, her reporting has been honoured by the Canadian Community Newspaper Awards, the Ontario Community Newspaper Association and the Local Media Association.